Federal efforts to roll back clean energy incentives—most notably through H.R.1, the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill”—are unlikely to derail the energy transition underway in MISO in the near term. That’s because state-level policies in clean energy leaders like Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois remain intact, and most new generation additions must first navigate a multi-year interconnection process.

With the MISO queue already backlogged and supply chain constraints delaying both renewable and fossil fuel projects, the immediate opportunity lies in accelerating the development of renewable projects that already hold signed Generator Interconnection Agreements. These projects—primarily solar—are MISO’s best shot at maintaining reliability amid coal retirements and federal policy uncertainty.

Watch for signals from Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois

Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois are the states to watch within MISO when it comes to energy policy, especially now that the federal government is scaling back Inflation Reduction Act incentives through H.R.1, (the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’).

In contrast, states like Indiana, where policymakers have attempted to classify coal as renewable, continue to lag on clean energy progress. But MISO’s own analysis shows that new capacity will be needed soon due to ongoing coal plant retirements. While delaying those retirements is one possible response, that option depends heavily on state-level policies. It’s hard to see why states with enforceable decarbonization goals like Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois would reverse course.

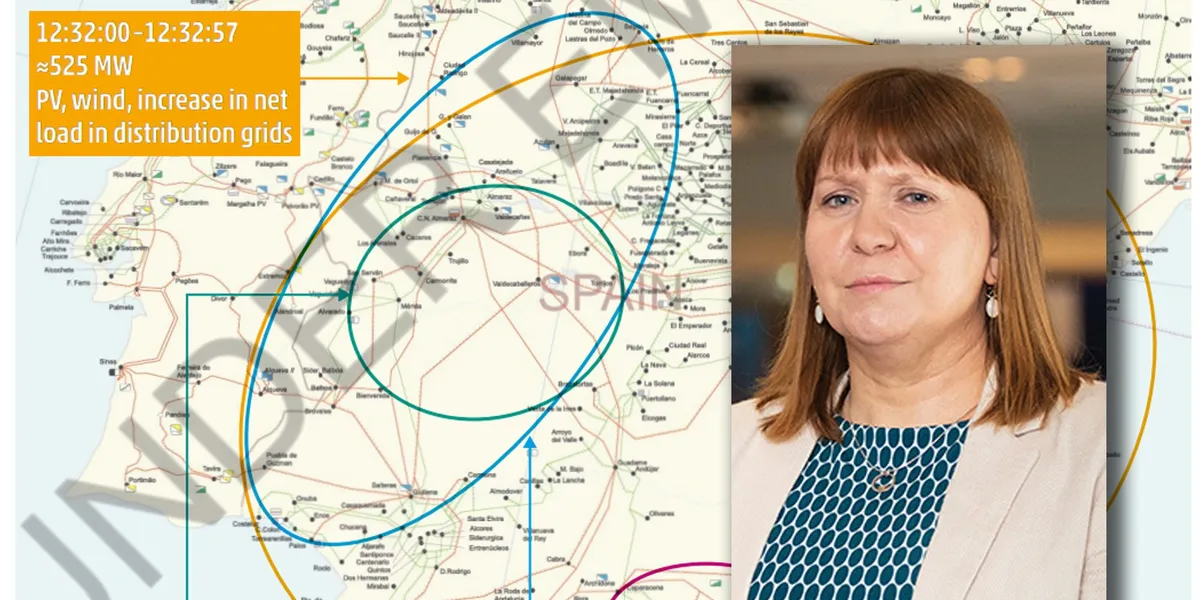

Former North Dakota PUC Commissioner Julie Fedorchak, now in Congress, remains a strong advocate for fossil energy. MISO, as a multi-state RTO, must balance divergent energy policies—from fossil-friendly states like North Dakota and Indiana to clean energy leaders like Minnesota and Illinois.

But MISO cannot ignore state-level decarbonization mandates. The MISO Board has already approved Tranche 1 and 2 transmission plans that explicitly reflect those clean energy targets. Even as MISO pauses Tranche 3 and 4 to revisit its Futures process, it still has an obligation to support its Transmission Owners in state CPCN proceedings—many of which are built on those same policy goals.

The current federal administration may push through legislation like H.R.1, but its effects on clean energy projects in MISO’s generator interconnection queue will take years to materialize. Projects already in Definitive Planning Phase 3 are, in my estimate, not at risk. The real impact will fall on projects that haven’t even entered the study process yet.

Renewable developers may want MISO to expedite the queue, but that’s not feasible given the existing backlog. And that same bottleneck will delay any new fossil fuel plants, too—natural gas projects included. For example, projects entering MISO’s 2025 queue are currently scheduled to reach a signed Generator Interconnection Agreement (GIA) by February 2027. But that timeline isn’t realistic. MISO is still studying projects from the 2020 cycle, and based on current pace, I estimate that 2025-cycle projects won’t reach GIA execution until 2029—because MISO won’t even begin studying them until Q1 2026.

By then, the political landscape may shift again, potentially bringing more favorable federal policy toward clean energy. In the meantime, solar projects that have been sitting in the queue for the past 3–4 years will likely reach GIA execution. Most of these are renewables—especially solar—and will be the only viable resources ready to support grid reliability.

That’s why a case must be made: regardless of federal turbulence from H.R.1, MISO must recognize that its immediate capacity solutions lie in the renewable projects already far along in the queue.

Supply chain constraints compound this problem. As Politico reports that NextEra CEO John Ketchum recently said at CERAWeek, “To get your hands on a gas turbine right now and to actually get it to the market, you’re looking at 2030 or later. The cost of gas-fired generation has gone up more than threefold.”

This statement carries particular weight because NextEra is one of the top five renewable developers in the MISO footprint. If even a company of that scale and influence can’t secure GE Vernova gas turbines, what chance does a small utility have?

The Waiting Game

So, the MISO queue backlog isn’t the only bottleneck for new gas plants, as supply chain constraints are equally limiting. Ironically, it’s the same kind of supply chain disruption that delayed renewable projects in the aftermath of COVID. Many MISO projects with signed Generator Interconnection Agreements (GIAs) are still struggling to reach commercial operation due to lingering impacts from that period.

That’s why MISO is increasingly concerned about the number of signed-GIA projects that remain inactive. States should be focused not just on chasing new capacity—however politically attractive that may be—but on ensuring that already-approved projects don’t fall through the cracks. The real near-term reliability solution lies in converting signed GIA capacity into steel in the ground.

Rather than chasing new capacity that may not materialize for years, state regulators and policymakers should focus on converting signed-GIA projects into operational assets. MISO’s ability to maintain grid reliability in the coming years will depend not on hypothetical gas plants or political signals from Washington, but on whether the renewables already in the pipeline can get built. That means tackling permitting, interconnection delays, and construction headwinds now, while the opportunity is still viable.